Originally at https://www.educationnext.org

Textbooks tell us that political parties pursue power, interest groups protect their welfare, and think tanks conduct research on policy-relevant topics. These distinctions have never been absolute. Historically, parties adopted platforms designed to win elections; think tanks have always had a partisan coloration. But lines that differentiate these types of political organizations blur today as never before.

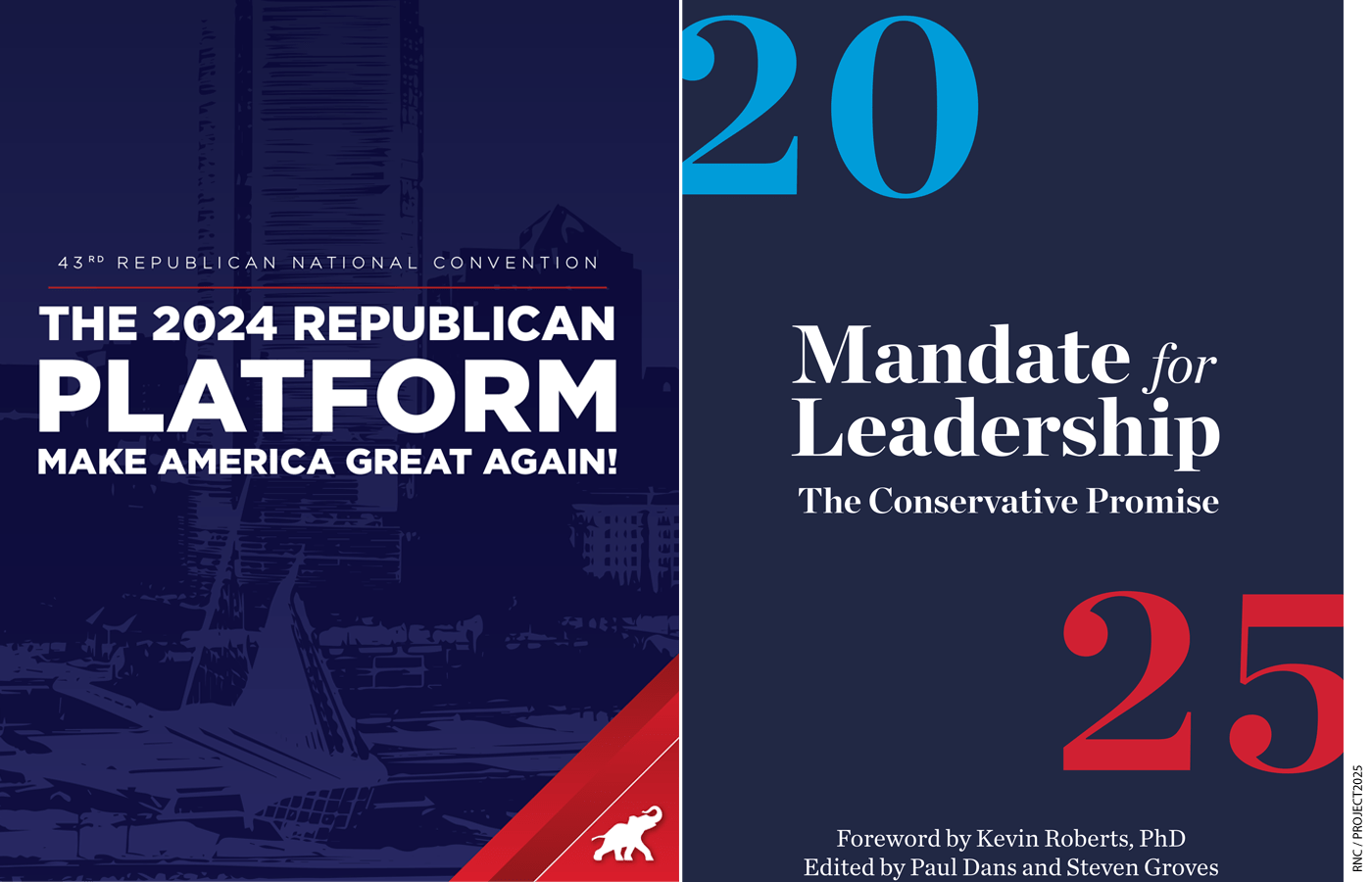

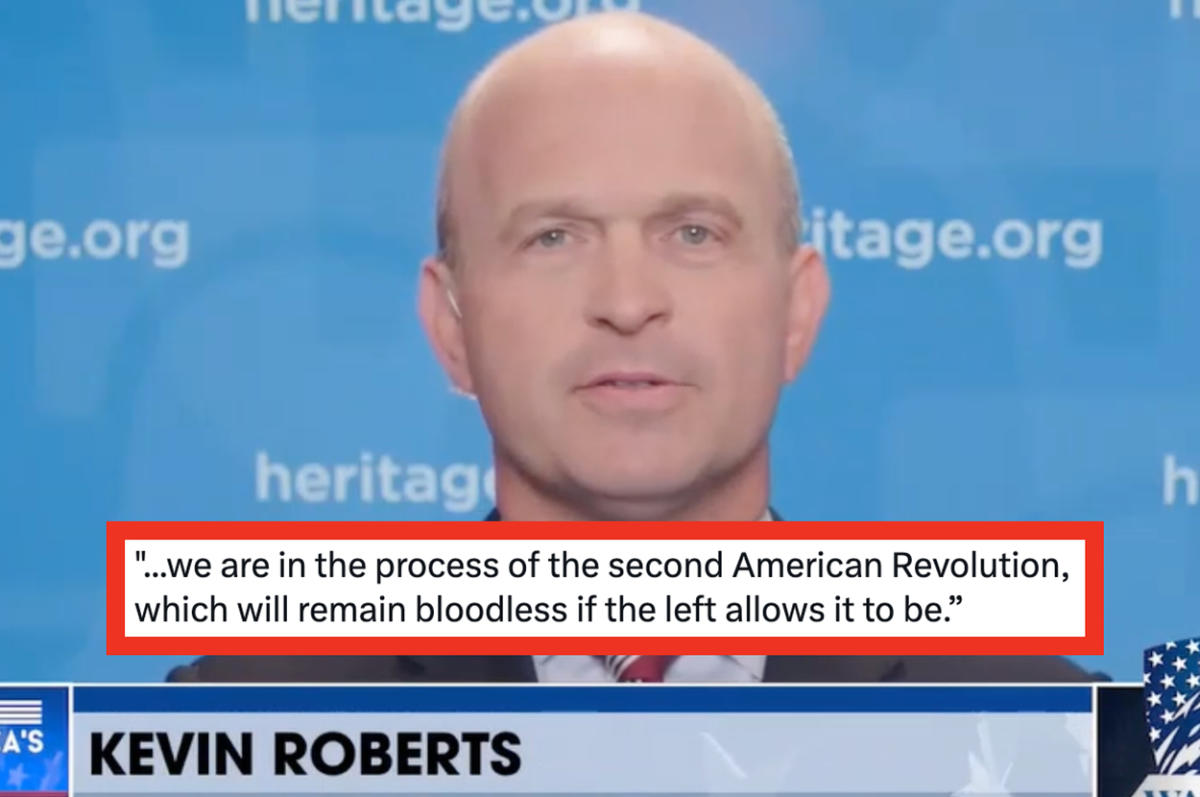

This election year, Democrats are accusing Donald Trump of running on a platform written by the Heritage Foundation, a conservative think tank known for its policy advocacy. They point out that nearly 200 of those involved in drafting Mandate for Leadership: The Conservative Promise, a 900-page report produced as part of the foundation’s 2025 Presidential Transition Project (commonly known as Project 2025), served in the first Trump administration. The chapter on education was written by Lindsey Burke, a long-term Heritage staffer, though she acknowledges help from former members of the Trump administration, including Jim Blew, who served as Assistant Secretary for the Office of Planning Evaluation and Policy Development. But Donald Trump denies that Mandate serves as a guide for his presidential plans, saying it is merely the “wish list” of policy advocates and that “some of the things they’re saying are absolutely ridiculous and abysmal.”

The probable truth—only future historians will know for sure—lies somewhere between Democratic accusations and Trump denials. A comparison of the K–12 plank in the platform just adopted at the Republican convention with the K–12 recommendations included in Mandate’s education chapter finds few contradictions between the two documents—though Project 2025 goes into vastly more detail than does the document approved by the delegates in Milwaukee.

The most obvious difference between the two texts is their length. The platform’s K–12 education plank is barely a page long, while the Heritage education chapter runs over 40 printed pages. Clearly, the party wants to say little that could stand in the way of achieving power; the think tank wants that power turned into policy.

But does Heritage tell us the true meaning of the vague words contained in the Republican national platform? The answer is closer to “it depends” than either “yes” or “no.”

The party platform’s education plank is hardly meaningless. Although it contains a lot of “mother and apple pie” language, such as “support schools that focus on Excellence and Parental Rights” and “prepare students for great jobs and careers,” it delineates sharp disagreement with policies favored by many Democrats and the Biden administration. Mandate offers dozens of education policy recommendations, large and small, but some of them address major issues also considered in the platform. To assess the strength of the Democratic accusations and Republican denials, let’s compare how the two documents address six topics: federal spending, the future of the U.S. Department of Education, school choice, special education, civics education, and race and gender issues.

Federal Spending. Mandate takes a clear, strong position on federal spending that is not explicitly shared by the Republican platform. The latter claims the United States spends more money on schools than any other nation, but it fails to promise any cuts to K–12 expenditure, thus sparing the national ticket from charges that it is set on starving the public school. Mandate, on the other hand, calls for the elimination of a wide range of federal education programs, estimated to save nearly $20 billion annually, and proposes that “[o]ver a 10-year period, the federal spending [on compensatory education, the largest federal program] should be phased out.”

Abolishing the U.S. Department of Education. Though the platform treats spending levels sub silentio, it boldly resurrects Ronald Reagan’s proposal to shutter the U.S. Department of Education. About what to do with all the education-related activity that must continue somehow, the platform says nothing. One must assume Republicans expect some other federal agency to take over the job—as was the case before Jimmy Carter and Congress created the department in 1979. Mandate does not differ in principle, but it is good deal more realistic when it proposes that the department be gradually eliminated over the course of the next decade and offers suggestions as to which agencies could do the same job more effectively. As programs are phased out, federal funding should take the form of no-strings-attached block grants to states, it says, though it also recommends that states be asked to distribute the funds to parents to be used at the school of their choice.

Read the Original Story